Static Analysis

In this new series, I’ll be going through the process of analysing malware starting off with static analysis.

The malware I will be analysing is a Bitcoin miner which I obtained from — https://github.com/fabrimagic72/malware-samples

The reason I chose the Bitcoin miner file is because of the current upsurge of the price and news of Bitcoin.

Most of the static analysis I do is already scripted in Python which you can see here:

https://github.com/cchaq/MalwareAnalysis-MonnappaKA/blob/main/static_analysis_ch1.py

So I won’t be running through any of the code, this will just be an analysis of the results. Also, I go through this process on a Linux box but the same steps can be taken on a Windows machine using a multitude of malware analysis tools.

Analysis of 02ca4397da55b3175aaa1ad2c99981e792f66151

So the name of the Bitcoin miner file is called 02ca4397da55b3175aaa1ad2c99981e792f66151, which tells us nothing and that is expected if the threat actor wants to keep it ‘dark’.

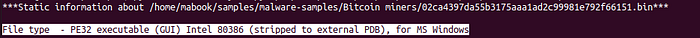

- Let’s determine the file type —

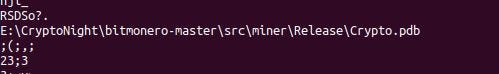

We can see it is a PE32 (Portable Executable) executable and it’s 32-bit. It says that it’s “stipped to external PDB” which means that the compiler builds a second program database but removes certain symbols. (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/reference/pdbstripped-strip-private-symbols?view=msvc-160).

Doing ‘xxd -g 1 file | more’, we see that the first 2 bytes are “4d 5a” which translates to ‘MZ’ (Mark Zbikowski).

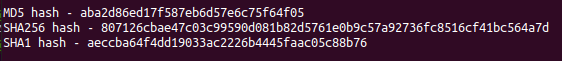

2. Next, we’ll generate some cryptographic hashes of the file:

We can use these hashes and run them through Virus total to see if we get any hits(Spoiler alert: We do). I’ve created a function in my script to query the Virus Total API but you will need your own key to access their API.

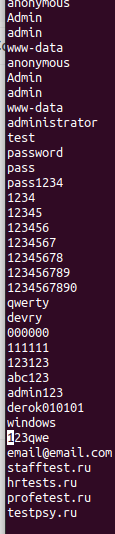

3. Now let’s run the “strings” program against the file to display the printable characters. Now I’ve run the strings program with the default settings and that spews out a lot of strings, but there are some interesting results:

We can see that this list comprises user names and passwords (www-data is a default web user for web servers) and ‘Admin’ ‘admin’ is normally used as default credentials for web services. This indicates some type of brute force to login into a system.

The ‘.ru’ is the Russian domain.

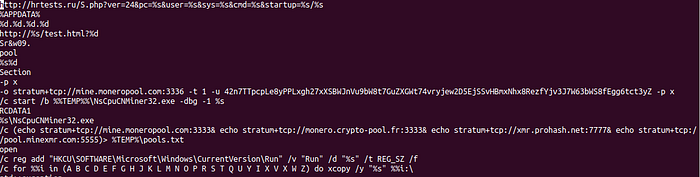

Here what I find most notable is “mine.moneropool” and Monero is a cryptocurrency, this indicates that this is built to mine Monero.

We can see it makes TCP connections, so when we do a dynamic analysis on this we should see these connections.

I’m not familiar with how to mine for Monero, but these API calls may be public but the string starting with “42n” may indicate that is a username. This is something that will need to be researched.

If that is a username or an authentication string, we could use that to do tracking.

We can see a “reg add”, so we know it adds to the registry.

And here we can see a file path. If came across this sample without any prior knowledge, we can use what we learn from Strings to make a good assumption that it is a cryptocurrency miner.

But we must stay open-minded because this may be the first Matryoshka doll.

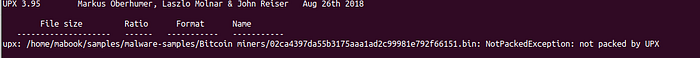

4. Now we will check to see if the file is packed:

‘upx -d -o cc_miner malware_file’ —

Well…..that was easy….

5. Now for a little of an in-depth look, let's take a look through the PE header!

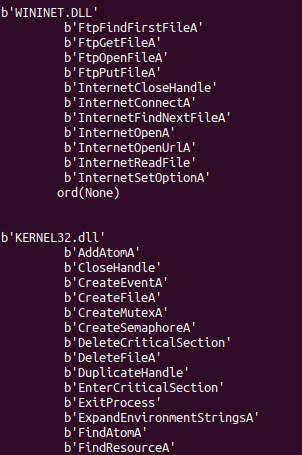

Using ‘pe’, we can extract the dll, imports, exports, and so on.

Here is the list of libraries the binary is using:

A. wininet.dll

B. kernel32.dll

C. msvcrt.dll

D.shell32.dll

If there is a library that you are unfamiliar with, then you would search that library on Microsoft's website: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/troubleshoot/windows-client/deployment/dynamic-link-library#dll-troubleshooting-tools

Once you locate the library, on the right-hand side you can see the list of it’s functions.

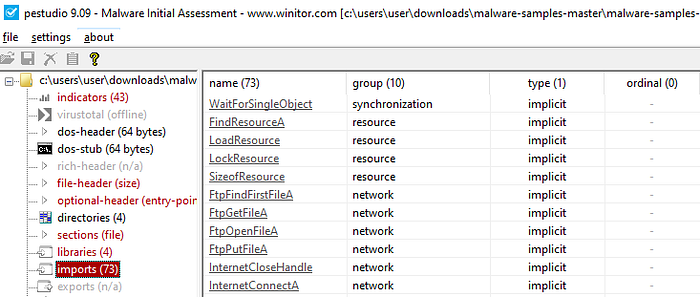

The functions used by the malware binary can be seen under the imports table:

This is not the full list but merely a snippet of the imports, but you can inspect them to get a good understanding of what the malware requires in order to achieve its goal.

Also it’s important to note what is not being used, for example, there are no imports to build a GUI, therefore we know that there is no UI to this binary.

I did run this binary through “pestudio” (just in case I missed something or my code needs updating) and we can see that it was 73 imports.

We could determine if a binary was packed if we saw a low number of imports, in this case, at this moment in time, I say it is not packed.

Now let’s take a look at the exports, which we can already see from above…there are none.

An executable and dll can export functions that can be used by other programs. Normally, the dll exports functions which are then imported by an executable. For example, if a threat actor was able to successfully replace a dll with a malicious dll on a victim's machine, then a running process could then import a function from the malicious dll, unknowing that it’s been replaced, and execute malicious code.

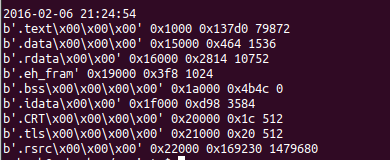

5.1. Now let’s examine the PE section table and sections:

Not very pretty I know, but it’s on my to-do list. So I went through the section using ‘pestudio’:

A lot cleaner….

The first thing which I noticed that the raw-size and the virtual-size are roughly the same. Another indication that it’s not packed

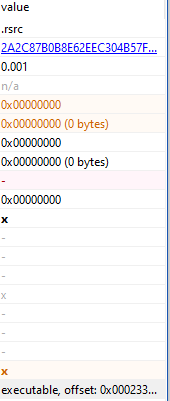

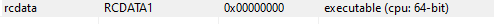

And….there is this in the .rsrc (resources section):

In the resources tab in ‘pestudio’:

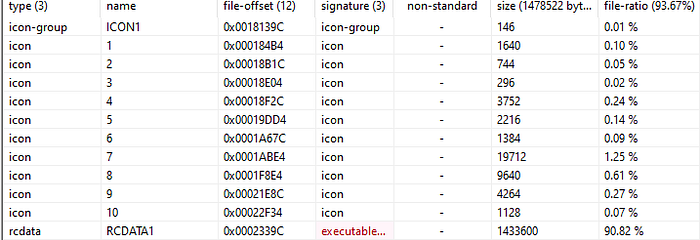

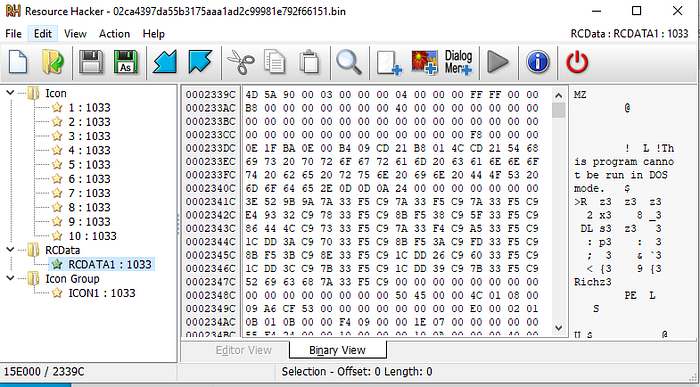

To examine this further I need to run the binary through ‘resource hacker’ —

The hidden executable size is 90% of the original binary.

Well….looks like there is an executable packed into the malware binary we have been analysing.

We can use resource hacker to save the binary within ‘RCData’ and then load it into ‘pestudio’.

And there we have another binary we need analyse, but I won’t do that in this writeup.

Conclusion

From the static analyse we have determined that this is a Bitcoin (Well, Monero) miner (so no surprise there) and it contains an executable within its resource section that needs analysing.

Using what we learned we can write up YARA rules by using the results from “strings”, ‘pefile’ and to look for the hex of ‘MZ’ within the .rsrc file (using the offset).

So next up I will do a dynamic analyse of the binary file we’ve been analysing and using what I’ve learned here I can keep a close eye on certain actions the binary performs.

Comments

Post a Comment